In many professions, specific terms – both old and new – are often established and accepted unquestioningly, from the inside. In some cases, such terms may create and perpetuate inequity and injustice, even when introduced with good intentions. One example that has played on my mind over recent years is the term ‘second victim’.

The term ‘second victim’ was coined by Albert W Wu in his paper ‘Medical error: the second victim’. Wu wrote the following:

“although patients are the first and obvious victims of medical mistakes, doctors are wounded by the same errors: they are the second victims”.

As someone with a PhD in ‘human error’, the potential for trauma associated with one’s own actions and decisions is a phenomenon that I have come across in many interviews and discussions, albeit in a different context – air traffic control. In this context, professionals’ decisions and actions are almost never associated with death, but there are rare examples, and the prospect of hundreds of lives being lost at once can be devastating in the context of a near miss.

The term ‘second victim’ in healthcare was further popularised by Sidney Dekker in his 2013 book Second Victim: Error, Guilt, Trauma, and Resilience. There are tens of thousands of webpages on ‘second victims’. It is a term that is accepted by healthcare practitioners who see only too clearly the immediate consequences of mistakes and actions-not-as-planned.

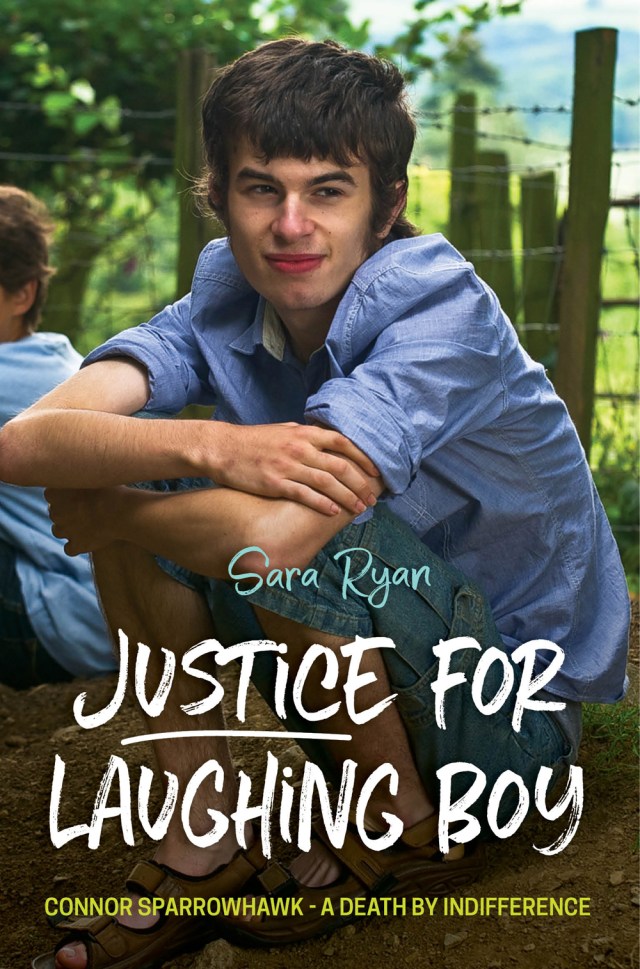

While the term is accepted within the medical professions, important questions have been asked by those who have lost more than their confidence, profession or even – for however long – mental health. Sara Ryan – the mother of Connor Sparrowhawk (popularly known as LB, or Laughing Boy), is one of several families who have questioned the use of the term in healthcare. Sara remarked on twitter:

Not heard of that phenomenon.

— Dr Sara Ryan (@sarasiobhan) August 28, 2016

The thread continued:

Mm. Surely not ‘second victim’…

— Dr Sara Ryan (@sarasiobhan) August 28, 2016

She later clarified:

Surely families are the second victim?

— Dr Sara Ryan (@sarasiobhan) December 6, 2017

Surely families are the second victim? It was one of those questions that could perhaps only come from the profound truth of pain. LB was “a fit and healthy young man, who loved buses, London, Eddie Stobart and speaking his mind” (see the #JusticeforLB website). As described on #JusticeforLB:

LB’s mood changed as he approached adulthood and on 19 March 2013 he was admitted to hospital, the STATT (Short Term Assessment and Treatment Team) inpatient unit run by Southern Health NHS Foundation Trust). LB drowned in the bath on 4 July 2013. An entirely preventable death.

Sara Ryan

Sara and her family were not only victims following the death of Connor. They were further victimised by organisations responsible for Connor’s death. The process of getting justice has involved an inhumane ordeal, including a good deal of ‘mother blame’, detailed in Sara’s book ‘Justice for Laughing Boy’. This is a book that should be standard reading on a wide range of courses, from medicine to law. But in a paragraph, from the website #JusticeforLB:

How are you all doing?

Mmm. Good question. Not sure really. I can probably only speak for myself [Sara]. Not brilliant really. The death of a child is an unimaginable happening. That it could have been so simply and easily avoided, in a space in which no one would have thought he was at risk of harm, is almost impossible to make sense of. The actions of Oxfordshire County Council and Southern Health NHS Foundation Trust since his death have been relentlessly battering.

So perhaps it takes an experience of being a real second victim, and of being victimised, to see that the the term ‘second victim’ is one that only applies to loved ones.

Then again, it’s obvious. Of course family are the second victims. How could they not be?

But it is not obvious to tens of thousands, perhaps hundreds of thousands or more, of healthcare workers who find personal meaning in the term ‘second victim’, as applied to themselves – actually or potentially.

I asked my partner – an experienced practising psychotherapist and trainee counselling psychologist – what came to mind with the term ‘second victim’. Without hesitation, she said “family“. She had never heard the term ‘second victim’ before and did not know why I was asking.

She said, “If you’d have said ‘secondary trauma’, I’d have said the professional“. That is because, in this sense, the primary trauma is with the family who survive a person who has died. She also mentioned the difference in choice and control between clinicians and family, in that a clinician for instance, while unable to control the environment and resources, has control over whether she or he is a clinician. While my partner has no control over clients, she has control over her choice to remain a psychotherapist.

Some have tried to combine those who have died and their families as first victims (e.g., https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YeSvCEpg6ew). But this casual combination of the dead and their loved ones is unconvincing, and seems like a fudge. My own mother died at 45 years old (following delays in treatment and lack of communication between a private and public hospital, which I won’t go into here). I remember my father at the time saying, “People tell me they feel sorry for me. I say they should feel sorry for her. She died at 45!”

There is a very real difference between a someone who has died, and a loved one who is grieving for that person, and someone who is suffering having witnessed or somehow been involved as a healthcare professional before the person died. Sara writes more about that here. She notes that “I’m not ignoring or denying that healthcare staff may/must be devastated by the death or serious harm of a patient here. It simply ain’t comparable to the experiences of families.”

Questions about first and second victims inevitably imply a ranking. So if loved ones are the real second victims, different in a very real sense to the deceased, then where does this leave professionals, who are different in a very real sense to bereaved families? Logically, however unsavoury the ranking exercise, professionals are third victims. The conversation in the third tweet above continued on this line of inquiry:

Mmm. Not sure that touches bereavement and possibly should be third in line morally.

— Dr Sara Ryan (@sarasiobhan) December 6, 2017

Completely agree about support needed, just seems that families are discounted and drs prioritised.

— Dr Sara Ryan (@sarasiobhan) December 6, 2017

While ranking victimhood may seem like a troubling exercise, professionals in healthcare have, in effect, already created a ranking by establishing – quite uncritically it seems – the term ‘second victim’. ‘Second victim’ indicates a first victim, and implies a third victim.

During bereavement, families are sometimes victimised further still by organisations during the natural quest for justice. Justice, in this context, includes apology, truth, genuine involvement, learning, and change. For LB and his loved ones, it included this and this. In effect, justice involves the proper meeting of needs. There are millions more like LB, and millions of families like his, who feel forgotten and discounted by the professionals, organisations, and society, who morally and ethically should be involved in meeting these needs.

Sadly, the established ‘second victim’ concept, in effect, further victimises the forgotten. Acknowledging and helping to meet the needs of loved ones as the real second victims, as well as healthcare professionals as third victims, would be a truly restorative act of justice.

Reference

Wu, A.W. (2000). Medical error: the second victim. The doctor who makes the mistake needs help too. British Medical Journal, 320, 726–727.

Fantastic piece, real food for thought. As someone who deals with and tries to support both families and healthcare staff involved in poor outcomes following unintended / unplanned actions, I agree we need better terminology and better concepts for understanding the challenges and the support needed.

LikeLike

Thank you – very interesting

LikeLike