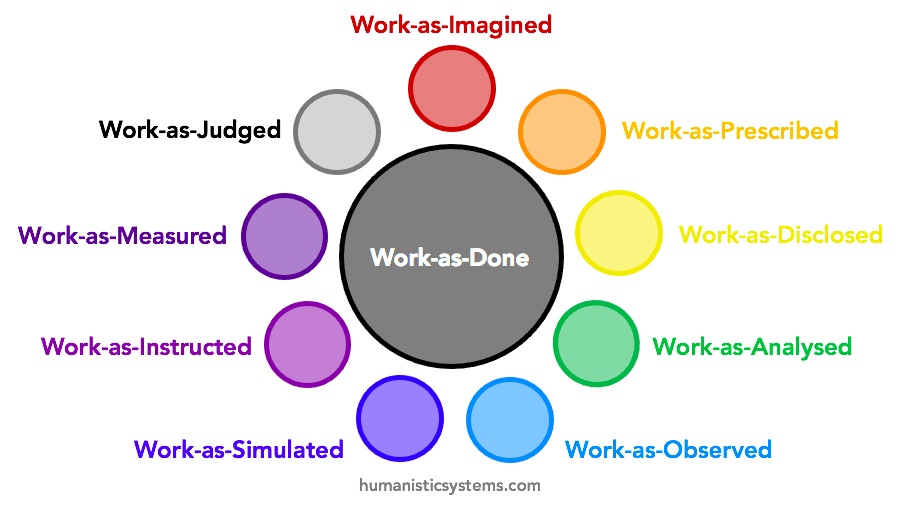

In any attempt to understand or intervene in the design and conduct of work, we can consider several kinds of ‘work’. We are not usually considering actual purposeful activity – work-as-done. Rather, we use ‘proxies’ for work-as-done as the basis for understanding and intervention. In this series of short posts, I outline briefly some of these proxies. (See here for a fuller introduction to the series.)

Other Posts in the Series

- Work-as-Imagined

- Work-as-Prescribed

- Work-as-Disclosed

- Work-as-Analysed

- Work-as-Observed (this post)

- Work-as-Simulated

- Work-as-Instructed

- Work-as-Measured

- Work-as-Judged

Work-as-Observed

Work-as-observed is the observation of the work of others, formally or informally, and the interpretation of what is observed by the observer.

Function and Purpose: Work-as-observed involves attending to, monitoring and perceiving the work of others, formally or informally, and the interpretation and direct description of what is observed by the observer. It may involve any of the senses, not only visual observation. Work may be observed in the context of real operations (work-as-done) or simulated environments (work-as-simulated). Work-as-observed is usually intended to help understand how work is really done, as a basis for one or more of the other proxies, but it may also be more casual, such as a patient observing the work of hospital staff. It may include any aspects of behaviour, interactions between people and other aspects of the work system (e.g., communication), events of interest, and aspects of context. Work-as-observed has various purposes concerning work design (e.g., procedure design and evaluation), artefact design and evaluation (e.g., interface design and evaluation), facility design (e.g., room layout), job design (e.g., job descriptions), competency and training (e.g., simulator session design, performance evaluation criteria), and safety and quality (e.g., error analysis, quality improvement), and supervision and management generally. In the case of casual observation, it may have no particular purpose, since we all observe others’ work, as co-workers, customers, patients, etc.

Form: Work-as-observed may be done informally or using formal methods, especially as an input to work-as-analysed. Some formal methods are sector-specific, such as line operations safety audit (LOSA; aviation), day-to-day safety observation (air traffic control). Other formal methods are sector-independent but still work-oriented (including methods from human factors and ergonomics, psychology, sociology, anthropology, practice theory, etc). Methods may focus on work generally, or particular aspects of work such as pre-defined interactions, which may be revised as observation progresses. Methods may be unobtrusive (‘hanging out’), or rather obtrusive (e.g., think aloud technique, verbal protocol analysis), and may include questioning, conversation, and checklists, perhaps requiring counts of specific interactions. Equipment may be used to aid work-as-observed, such as eye movement tracking, sensors, or video recording. There may be some degree of interpretation or inference beyond what is directly observable, for instance considering who has more influence. Field notes and diagrams are usually taken with formal methods, which may be brief during observation but refined afterwards.

Agency: The work of others is observed by all of us in a casual or informal way. But work is often observed more formally by specialists in professions or functions such as human factors and ergonomics, work psychology, user research, training, competency assessment, safety, quality, and operational support roles (such as supervisors). Work may be observed from insider or outsider perspectives, with varying degrees of observer participation in the work context.

Variety: Work-as-observed is limited to the activity that is actually observed. However, what is observed will tend to differ among different observers, and for the same observer using different methods, even for the same work situation. This is because of various factors associated with observers and those observed, activities, tools, and contexts. For instance, an observer’s understanding will be strongly influence what the observer looks for, sees and hears, how they interpret it, and what they understand, remember, record and query. The focus of attention – zooming in on the details or zooming out to the context – will also influence what is observed and understood, as will the observer’s state (e.g., alertness), and whether recording is live and in situ, or via an audiovisual recording with playback functionality. Reliability of observations between different observers and for the same observer over time is difficult to assess, except for specific circumstances where the scope of observation is highly specified (e.g., specific physical interactions with an interface).

Stability: Work-as-observed (as a kind of work-as-done in itself) changes over time, just as the work-as-done of others changes. The reliability of observations changes, just as the reliability of task performance generally changes, over time and in different conditions.

Fidelity: Work-as-observed is meant to help understand the work-as-done being observed, and so serves to update work-as-imagined and function along with other proxies (e.g., work-as-disclosed). However, it is not possible to observe all aspects of work-as-done, except for observable aspects of very simple tasks. This is because of: a) the variable nature of work-as-done (between different individuals and by the same individuals over time and in different situations), meaning that it is not often possible to observe enough to get anything like a ‘complete understanding’, b) interdependencies and conditions influencing work-as-done, meaning that again not all conditions can usually be observed, especially for complex, dynamic tasks, c) the dynamic and covert nature of work-in-the-head (e.g., task switching, risk assessment, planning, judgement), d) limitations in terms of methods and the competencies required. When observing people at work, we are usually only able to focus on one thing at a time (recordings may help here), and so this limits what can be observed. And we may choose to focus on certain aspects of the observation space, such as errors or interactions with a human-machine interface. So what can be observed is a limited aspect of work-as-done. Much will be missed, without even realising. Fidelity is also strongly associated with the characteristics of the observer (e.g., skills and knowledge, language, identity, style of dress), the communication and relationships between the observer and the observed (especially trust, which may require prolonged engagement), degree of observer participation and intervention, the method(s) used, and the representativeness of the people and work situations observed to the range of people and work situations that are and may be experienced as work-as-done (this may change unpredictably or predictably but over a long period, such as seasonally).

Completeness: Work-as-observed may focus on all of part of a task or job, depending on the boundary of analysis, but at different levels of granularity. One may try to observe everything and anything (descriptive observation, with no prior agenda), or observe selectively, based on other proxies for work-as-done such as work-as-disclosed (e.g., prior interviews). work-as-analysed (e.g., task analysis), or work-as-prescribed (e.g., a procedure or interaction design). As noted above, not all aspects of work-as-done can be observed, and so work-as-observed will never be complete. Again, this especially applies to work-in-the-head. Taking detailed field notes will also reduce what can be observed, since it is. not usually possible to attend to two things at once. Using a variety of methods for observation can help to provide different perspectives on the work, and thus forms a more complete representation. It also more difficult to observe certain roles, for practical and social or political reasons. While a train driver may be observed, the CEO of a train company usually cannot be observed so readily, and not in the same sort of way. For this reason, behavioural observation at work rarely focuses on anyone other than operational staff.

Granularity: Work is observed at different levels of granularity for different purposes and in different contexts. Granularity will vary from general impressions (e.g., of work context, taskload or work tempo), through quality of communication, to observations of specific interactions (e.g., speech communication; interactions with user interfaces or tools).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0