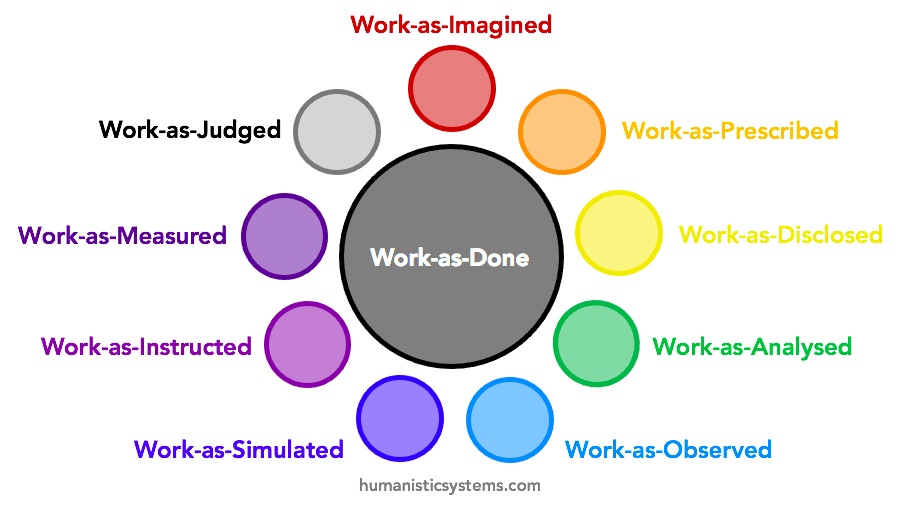

In any attempt to understand or intervene in the design and conduct of work, we can consider several kinds of ‘work’. We are not usually considering actual purposeful activity – work-as-done. Rather, we use ‘proxies’ for work-as-done as the basis for understanding and intervention. In this series of short posts, I outline briefly some of these proxies. (See here for a fuller introduction to the series.)

Other Posts in the Series

- Work–as–Imagined

- Work-as-Prescribed

- Work-as-Disclosed (this post)

- Work-as-Analysed

- Work-as-Observed

- Work-as-Simulated

- Work-as-Instructed

- Work-as-Measured

- Work-as-Judged

Work-as-Disclosed

Work-as-disclosed is the work that people say that they (or others) do or did, either in formal accounts or informal accounts.

Function and Purpose: This is what we say and write about work, and how we talk and write about it. It may be simply how we explain the nitty-gritty or the detail of work, or give a particular view or impression of work (as it is or should be). It serves an intention and need to describe or explain work to others to influence any of the other proxies for work-as-done (e.g., others’ work-as-imagined, work-as-prescribed, work-as-analysed, or work-as-judged).

Form: Work-as-disclosed may be more formal or more informal, in written and verbal forms. It includes what is said or written, and what is not. More formal methods of disclosing aspects of work include interviews, workshops and focus groups, surveys, incident and accident reports, audits, inquiries, press releases, official statements, corporate communications, social media, etc. These may be for organisational, regulatory or scientific purposes. More informal methods include general conversations. Somewhere in-between are handovers, completed checklists and other methods of disclosure on the job. Work-as-disclosed may be in the context of work-as-done (e.g., demonstrating work to a new member of staff; think aloud technique) or remote from work-as-done (e.g., incident report; critical incident technique).

Agency: Work can be is disclosed by anyone, both those who do the work, and those who do not. Some work-as-disclosed is based on (or disclosed with) intimate knowledge of work-as-done and by those who do it. Other work is disclosed by people who know very little about it.

Variety: Work can be disclosed in a wide variety of ways even in the same form, such that the same work is described quite differently by the same or different people. This will depend on various aspects of the context (e.g., the parties to the disclosure, the purpose of the disclosure, the knowledge and recollection of work-as-done, the time and events since work-as-done, and the imagined consequences).

Stability: Work-as-disclosed may change significantly over time (for the same sorts of reasons as noted in ‘Variety’ above). For example, our work-as-imagined of our own work-as-done is a reconstruction, rather than a recording, and this reconstruction will change over time as we try to make sense of the work (or make it seem sensible). We forget details over time and also change what we say to suit particular purposes or respond to imagined consequences (see ‘Fidelity’ below).

Fidelity: The celebrated US Anthropologist Margaret Mead was credited with saying “What people say, what people do, and what they say they do are entirely different things” (there is no written evidence that she every did say this, but it is reflective of aspects of her work). Work-as-disclosed and work-as-done are not necessarily quite so detached, but work-as-disclosed differs in important ways (not just granularity) from work-as-done, and for many reasons.

What we do at work may be different to what we are prepared to say, especially to outsiders or ‘outgroup’ members. What a staff member says to a senior manager or auditor about work may be different to what really happens, for example. There are many reasons not to express how work is really done. But people will tend to modify or limit what they say about work-as-done based on imagined consequences. For instance, staff may fear that resources will be withdrawn, constraints may be put in place, sanctions may be enacted, or necessary margins or buffers will be dispensed. So secrecy around work-as-done may serve to protect one’s own or others’ interests.

This is especially evident when people have to disclose the circumstances of failures or non-compliance with work-as-prescribed. In an environment where there are sanctions for necessary trade-offs, workarounds, and compromises, work-as-disclosed may be more in alignment with work-as-prescribed than is really the case (for instance, in the context of some audits or investigations). This relates to the Taboo archetype. In some cases, there may be specific activities that people don’t want to reveal relating to unethical behaviour. Such practices will tend to violate prevailing norms (social, procedural, legal, moral or ethical) or expectations, and disclosure would be detrimental to the continuation of the practice. In such cases, work-as-disclosed may reflect the P.R. and Subterfuge archetype. Work-as-done may be described deliberately to influence others’ (especially outgroup members’) work-as-imagined in particular ways. This may extend to large scale cover-ups.

In other cases, work-as-disclosed is more subtly designed to reassure, with goodwill and based on what one imagined is in the best interests of the other (a form of paternalism).

In still other cases, there may not no intentional deceit on behalf of the discloser, but what is disclosed may be fed by subterfuge by others (reflecting the Ignorance and Fantasy archetype).

If there is a culture that is mutually experienced as fair and trusting, with acceptable levels of psychological safety, then there is a good chance that work-as-disclosed will be reflective of work-as-done. In such cases, the areas of lack of overlap may be limited to inconsequential minutia, or aspects of work that are not easily available to conscious inspection from the inside, bearing in mind that much human work is based on unspoken assumptions and norms, and activity that is not available to awareness.

Completeness: Work-as-disclosed, like work-as-prescribed, rarely forms a complete representation of anything other than very simple work-as-done. Typically, communication (i.e., what is said/written, how it is said/written, when it is said/written, where it is said/written, and who says/writes it) is tailored for a particular purpose (why it is said/written), and, more or less deliberately, to what is thought to be palatable, expected and understandable to the audience. As noted above, it is often based on what people want and are prepared to say in light of what is expected and imagined consequences.

Granularity: Work is disclosed at many levels of granularity, depending on the purpose of the disclosure. A supervisor might explain to a newcomer ‘how things work around here’ (work-as-done), in a summary form. A surgeon and an anaesthetist/anaesthesiologist, may advise a patient about a surgical procedure at high level. A corporate communications specialist may explain to the news media or via social media the work of staff as a thumbnail synopsis. What is said will reflect what is done, but at a low resolution. In such cases, work-as-disclosed will involve simplifications. In other instances, work-as-disclosed may be at high resolution. An example is a train driver explaining his or her work to a human factors specialist/ergonomist who is undertaking some form of task analysis (for training needs analysis, interface design, or safety assessment). Here, the driver will be thinking about his or her work in detail, and explaining it in great detail.

I’m loving these but now my oxford essay will be hard to write (riffing off your original diagram, which is brilliant,) now that you’ve explained in more detail so well 😄 #1st world problems

LikeLike