Twenty years ago, I completed my PhD on human factors in air traffic control. Part of the study involved developing a taxonomy to describe cognitive errors and associated performance shaping factors. The taxonomy was known as TRACEr (Technique for the Retrospective and Predictive Analysis of Cognitive Errors) and was designed to be used for a variety of purposes including incident analysis, observation, and, along with a task analysis, human error identification for new tasks (see Further Reading). TRACEr had been in development for six years and was tested with hundreds of incident reports, in real-time simulations, and design projects. Since the focus of the method was what went wrong, the language in TRACEr (and associated methods) was negative.

‘TRACEr-retro’ was broadly structured around errors (task error, internal error modes, and psychological error mechanisms), performance shaping factors, information (the subject of the error), and error recovery. Example ‘internal error modes’ include misidentification, prospective memory failure, incorrect decision, and selection error. These had associated ‘psychological error mechanisms’ such as spatial confusion, similarity interference, false assumption, and manual variability. Example ‘task errors’ include separation error, radar monitoring error, controller-pilot communications error, and aircraft transfer error. There was also a prospective version called ‘TRACEr-predict’, and TRACEr was later slimmed down to a lighter version (TRACE-lite). Ultimately, the method was developed further over time, and different versions were adopted in many air traffic management organizations throughout Europe and the world. It was also developed into versions for other contexts such as rail, maritime, and oil and gas.

Developers of methods (and theories) tend to become attached to them. This might seem a strange departure from the scientific ideal, but is very human. There are many barriers to new thinking, both personal (e.g., pride; fear of financial loss) and systemic (e.g., integration of tools in safety management systems; trademarking). But the developer of any method should have intimate knowledge of its shortcomings and therefore should be among the first to critique it. This attachment is one reason why many tools do not change over time despite changes in thinking. In the case of TRACEr, I had several concerns. One dawning realisation after PhD completion was particularly troubling. With a deficit focus on what goes wrong, I missed the opportunity more fundamentally to help understand what goes on, including what goes right and what’s strong.

Deficit-based language

Deficit-based taxonomies and tools are common in Human Factors and safety practice. Some of these taxonomies are generic while others are bespoke to organisations. These encourage a negative view of the human contribution to safety and do not help us to talk about how people create safety. I wrote about this ten years ago here. Abraham Maslow wrote in ‘Psychology of Science’ (1969) , “I suppose it is tempting, if the only tool you have is a hammer, to treat everything as is it were a nail.“ Deficit-based taxonomies can become for safety what the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders is for medicine: a lens through which to select and interpret phenomena.

To quote the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein (1921), “The limits of my language mean the limits of my world. All I know is what I have words for.” We don’t need to interpret this in a literal or hard way to accept the point that our language certainly influences how we think – analyse, categorise, compare, evaluate, and judge. As literary theorist Kenneth Burke put it, “A way of seeing is also a way of not seeing — a focus upon object A involves a neglect of object B” (1935, 1984, p. 49). Burke remarked that “the poor pedestrian abilities of a fish are clearly explainable in terms of his excellence as a swimmer.” A focus upon failure means a neglect of non-failure.

Errors are a typical focus for safety taxonomies, either as a starting point for analysis or as a central focus of explanation (or even an end point). This emerges from the way in which we typically think about incidents as being caused by ‘sharp end’ errors (the causal attribution equivalency of a recency effect) which were influenced by other ‘blunt end’ factors. This way of thinking can result in lots of attention paid to errors, described, classified and frozen in time (and what I sometimes refer to as a sort of error taxidermy), but considerably less attention to other ‘influences’. The depiction of work following investigation and analysis using deficit-based taxonomies is a particular kind of proxy for work-as-done that I refer to as work-as-analysed. This informs work-as-imagined and influences work-as-judged.

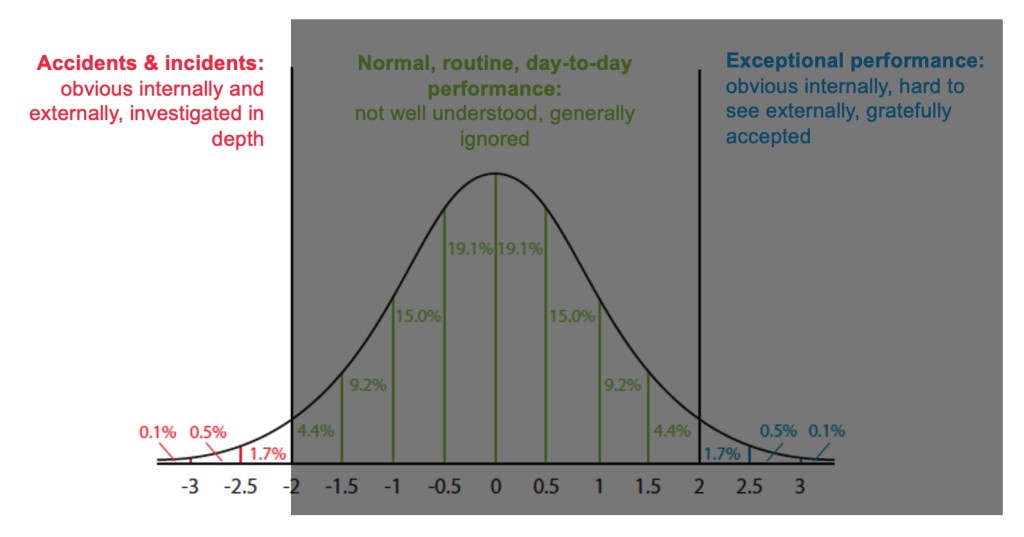

Deficit-based taxonomies can become weapons that can harm people and organisations, albeit in an attempt to improve safety. Negative language has a framing effect on conversations which acts as an analytical and discursive equivalent of hemispatial neglect – a neuropsychological condition characterised by deficits in perception and action on one side of space, usually after a stroke, which causes people to ignore half of their world. With deficit-based taxonomies, thousands of hours of everyday work – normal, routine, day-to-day performance – and even exceptional performance, are neglected, while a few minutes or even seconds in the context of an incident is analysed in depth using detailed deficit-based vocabulary. Deficit-based taxonomies provide no terms for ~99% of performance, but tens or perhaps over a hundred terms for less than ~1% of performance (these figures are illustrative). This results in a linguistic and conceptual dark zone for most of the opportunities for learning that exist. How do we describe how people work and how people create safety? How do we answer the question, “Why is our organisation operating well?” and – importantly – “What is it about how we do things that we value, and which we want to defend, retain and extend under pressure to be more efficient?”

Neutralised taxonomies

There are several possibilities to counter this. One is to abandon taxonomies altogether, perhaps using machine learning to draw insights from reports. This is a more complicated and radical option, which does not give a vocabulary to discuss work and organisational functioning, should one be deemed useful. Another simpler alternative is more pragmatic, and can be achieved readily with most taxonomies: neutralise the taxonomy. This involves removing adjectives and prefixes such as ‘poor’, ‘inadequate’, ‘incorrect’, ‘inappropriate’, ‘mis-‘, ‘error’, ‘violation’, and ‘failure’. So terms such as ‘incorrect decision’, ‘poor teamwork’, and ‘inadequate supervision’ become ‘decision’, ‘teamwork’, and ‘supervision’. These are not hindsight-based evaluative labels but terms about something that is relevant to a situation, which is worthy of discussion and reflection. They may be activities and conditions that perhaps did not go as well as we wished they had, with what we know now, or that perhaps contributed to a good outcome. After all, the difference between an incident an an accident is not necessarily just luck, but human intervention and associated conditions (e.g., training, procedures) that supported this intervention.

Neutralisation does not create a good taxonomy (the requirements for this can be found here), but it does create a better one – a more flexible and useful taxonomy – which can be used in several ways, for instance:

- Incident analysis. You can still use a neutral taxonomy to describe what went wrong, but you can also use it to describe what went well or simply what went on during an incident. This requires modifiers to indicate how a category is being used in terms of its role in an incident. This contribution could be more unfavourable or favourable, contributing more to the emergence of the unwanted situation or outcome, or to the recovery of the situation to a preferred state. Neutral terms can also be used more generally to analyse and describe activities and the context, regardless of the role that we might assign to the outcome. Importantly, there need be no loss of historical data following neutralisation of taxonomies, The old data can still be compared to newly coded data, given appropriate modifiers to indicate the contribution of each category to an incident.

- Other safety management activities. You can use a neutral taxonomy for other safety activities such as safety assessment, safety observation, safety culture discussions, and so on. Again, the focus becomes not deficits and failures but activities and conditions.

- Human Factors practice. Human Factors practice is characterised by the use of Human Factors methods and theory. A neutral taxonomy may include terms that are integrated into one of many Human Factors methods, for data collection (observational, interview, questionnaires, etc), task analysis, error analysis, situation awareness analysis, workload analysis, fatigue assessment, team assessment, design, etc. The taxonomy can act as a common thread between different methods.

- Systems thinking: Many systems thinking methods, such as system maps, influence diagrams, multiple cause diagrams, and AcciMaps, require the description of elements or components of the system of interest. You can use a neutral taxonomy to help with this.

- Training: A neutral taxonomy of activities and conditions can help to inform training programmes. Taxonomies concerning human performance may for instance comprise codes such as ‘decision making’, ‘memory’, ‘perception’, ‘communication’, or something similar. These facets of human performance, and the factors influencing performance, are relevant to various forms of safety related training such as crew/team/bridge resource management, emergency training, and surprise handling training. They may also be relevant to other training and education programmes in organisations on, for instance, neurodiversity, mental health, post traumatic stress, and major life changes where sensory, perceptual, cognitive or motor functioning may be affected.

Through these kinds of activities, neutral language helps to avoid unwarranted and harmful blaming language, counterfactual reasoning and hindsight bias concerning work to encourage learning and healing following unwanted events. A neutral taxonomy establishes vocabulary that may be used from incident reporting, through investigation and subsequent communication and learning.

Day-to-day conversations about work and organisational life are also likely to be improved. Conversations are shaped by the words we use, and taxonomies normalise certain terms. Neutral taxonomies focus on activities and conditions – what people do, how they do it, and what influences this. This may encourage a more holistic framing of the human contribution to safety – a net asset rather than a deficit. It is likely that a conversation about ‘decision making’ or ‘teamwork’ and the various influences upon these will be more productive and insightful than a conversation about ‘poor decision making’ and ‘inadequate teamwork’.

Finally, neutralised taxonomies can help to connect many otherwise disconnected organisational activities by providing a common language that may be used across different methods.

But it should be remembered that neutralising a bad taxonomy does not create a good one. The categories may be poorly designed, such that total redesign by a suitably qualified and experienced practitioner (with a focus on taxonomy, safety science and Human Factors) is needed. And even well-designed classification systems may be of limited value if other problems prevail, such as problems with reporting or the competency of of investigators. Neutralised taxonomies are not a a panacea, but may be a pragmatic adjustment that most organisations can make to their taxonomies to help widen the scope for learning.

Further Reading

Shorrock, S.T. (2002). The two-fold path to human error analysis: TRACEr lite retrospection and prediction. Safety Systems (Newsletter of the Safety-Critical Systems Club), 12 (1), September 2002. [pdf]

Shorrock, S.T. (2003). Technique for the Retrospective and predictive Analysis of Cognitive Error (full version). [xls]

Shorrock, S.T. (2003). Technique for the Retrospective and predictive Analysis of Cognitive Error (lite version) [xls]

Shorrock, S.T. (2005). Errors of memory in air traffic control. Safety Science, 43, 571-588. [pdf]

Shorrock, S.T. (2006) Technique for the retrospective and predictive analysis of human error (TRACEr and TRACEr-lite). In W. Karwowski(Ed.) International Encyclopedia of Ergonomics and Human Factors (2nd Edition). London: Taylor and Francis, pp. 3384-3389.

Shorrock, S.T. (2007). Errors of perception in air traffic control. Safety Science, 45, 890-904. [pdf]

Shorrock, S.T. and Kirwan, B. (2002) Development and application of a human error identification tool for air traffic control. Applied Ergonomics, 33, 319-336. [pdf]

Great perspective and practical tips on how to charge some of the “locked in” approaches for investigation or learning from incidents or even “better” preventive strategies such as applying to design of work. The relationship to binary language in general in our other methods and tools also come to mind

LikeLiked by 1 person