Sometimes lessons about work come about from the most wonderful places. Arnold Lobel’s ‘Frog and Toad’ books for children from the 1970s is one such place. Frog and Toad are friends, and share many everyday adventures. One of their adventures is recounted in a story called ‘A List’. The story starts with Toad in bed. Toad had many things to do and decided to make a list so that he would remember them. He started the list with “Wake up”, which he had already done and so he crossed it out. He then wrote other things to do. He followed his list and crossed each off, one by one.

After he got dressed (and crossed this off the list), Toad put the list in his pocket and walked to see Frog (and crossed this off the list too). The two then went for a walk together, in accordance with the list. During the walk, Toad took the list from his pocket and crossed out “Take walk with Frog”.

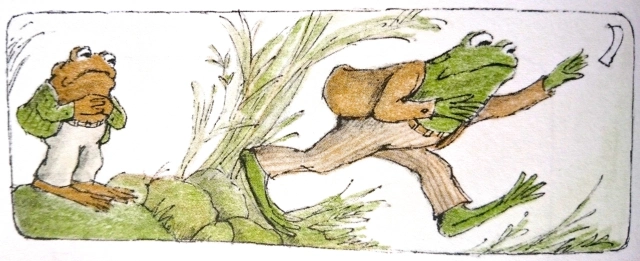

At that moment, a strong wind blew the list out of Toad’s hand, high up into the air.

“Help!” cried Toad.

“My list is blowing away.

What will I do without my list?”

“Hurry!” said Frog.

“We will run and catch it.”

“No!” shouted Toad.

“I cannot do that.”

“Why not?” asked Frog.

“Because,” wailed Toad,

“running after my list

is not one of the things

that I wrote

on my list of things to do!”

So Frog ran after the list, over the hills and swamps, but the list blew on and on.

Frog returned without the list to a despondent Toad.

“I cannot remember any of the things

that were in my list of things to do.

I will just have to sit here

and do nothing,” said Toad.

Toad sat and did nothing.

Frog sat with him.

Eventually, Frog said that it was getting dark and they should go to sleep, and Toad remembered the last item on the list:

Go to sleep.

Checklists are common in both everyday life and in complex and hazardous industries, such as aviation and medicine. They are sometimes seen as a panacea. They are certainly helpful, for many reasons: aiding memory, encouraging thoroughness and consistency, incorporation mitigations from risk assessments and investigations, and co-ordinating teamwork. But checklists cannot account for the total variety of situations that may arise, especially rare problem situations that perhaps have never been thought possible. In such cases, checklists may encourage an unhelpful dependency when fundamental knowledge and experience, pattern recognition, and indeed creativity may be required. Such events are sometimes referred to as ‘black swans’ (Taleb, 2010). Two of the characteristics of black swan events, according to Taleb, are:

“First, it is an outlier, as it lies outside the realm of regular expectations, because nothing in the past can convincingly point to its possibility. Second, it carries an extreme ‘impact’.”

One such black swan event occurred on 4 November 2010. Just four minutes after take off, climbing through 7,000ft from Singapore Changi Airport, an explosion occurred in one of the engines of QF32, a Qantas Airbus A380. Debris tore through the wing and fuselage, resulting in structural and systems damage. The crew tried to sort through a flood of computer-generated cockpit alerts on the electronic centralized aircraft monitor (ECAM), which monitors aircraft functions and relays them to the pilots. It also produces messages detailing failures and in certain cases, lists procedures to undertake to correct the problem. Nearly all the non-normal procedures are on the ECAM.

They crew recalled an “avalanche” of (sometimes contradictory) warnings relating to engines, hydraulic systems, flight controls, landing gear controls, and brake systems. David Evans, a Senior Check Captain at Qantas with 32 years of experience and 17,000hrs of flight time, was in an observer’s seat during the incident. Interviewed afterwards, he said “We had a number of checklists to deal with and 43 ECAM messages in the first 60 seconds after the explosion and probably another ten after that. So it was nearly a two-hour process to go through those items and action each one (or not action them) depending on what the circumstances were” (Robinson, 8 December 2010).

The Pilot in Command, Captain Richard de Crespigny (15,000hrs) wrote, “The explosion followed by the frenetic and confusing alerts had put us in a flurry of activity, but Matt [Matt Hicks, First Officer, 11,000hrs] and I kept our focus on our assigned tasks while I notified air traffic control … ‘PAN PAN PAN, Qantas 32, engine failure, maintaining 7400 and current heading’”… “We had to deal with continual alarms sounding, a sea of red lights and seemingly never-ending ECAM checklists. We were all in a state of disbelief that this could actually be happening.” (July 21 2012).

In an article in the Wall Street Journal, Andy Pasztor wrote that “Capt. Richard de Crespigny switched tactics. Rather than trying to decipher the dozens of alerts to identify precisely which systems were damaged, as called for by the manufacturer’s manuals and his own airline’s emergency procedures, he turned that logic on its head—shifting his focus to what was still working“. “We basically took control” said de Crespigny, “Symbolically, it was like going back to the image of flying a Cessna“. This strategy is reminiscent of Safety-II and appreciative inquiry, rather than focusing only on what is going wrong, focus on what is working, and why, and try to build on that.

When he was asked if he had any recommendations for Qantas or Airbus concerning training for ECAM messages in the simulator, Captain David Evans noted, “We didn’t blindly follow the ECAMs. We looked at each one individually, analysed it, and either rejected it or actioned it as we thought we should. From a training point of view it doesn’t matter what aeroplane you are flying airmanship has to take over. In fact, Airbus has some golden rules which we all adhered to on the day – aviate, navigate and communicate – in that order“. Similarly, Captain Richard de Crespigny noted “I don’t trust any checklist naively.” Rather than getting lost in checklists that no longer worked, he made sure that his team were focusing on what systems were working. On an Air Crash Investigations programme Qantas Flight 32 – Emergency In The Sky, he said “We sucked the brains from all pilots in cockpit to make one massive brain and we used that intelligence to resolve problems on the fly because they were unexpected events, unthinkable events.”

Checklists have been an enormous benefit in a number of sectors, especially aviation and now medicine, but we must remember that they can never represent all possibilities, as work-as-imagined will tend to deviate from work-as-done – through ineffective consultation, design, and testing, though incremental changes and adjustments, or through rare surprises and emergent system behaviour. That being the case, we must not forget about the importance of supporting and maintaining our human capacities for anticipation, insight, sensemaking, flexibility, creativity, adjustment and adaptation. In practical terms, this might mean:

- refresher training that is meaningful and challenging, and allows for experimentation in a (psychologically and physically) safe environment,

- information designed such that it meets our needs and does not exceed our capacity to process it properly,

- procedures that reflect the way that work is actually done, having been developed with users and tested in a range of conditions and re-checked over time – acknowledging that there will be a need for flexibility,

- a collective way of being that is fair and acknowledges the need to respond in unthoughtof ways, and

- some basic principles of work that everyone can agree on and fall back on.

With this in mind, we can make the most of checklists without beeing blindsided by them, like Frog and Toad. Instead, we can stay in control, or at least retain the ultimate fallback mode: human ingenuity.

Human ingenuity saved QF32 when the black swan flew by.

3 thoughts