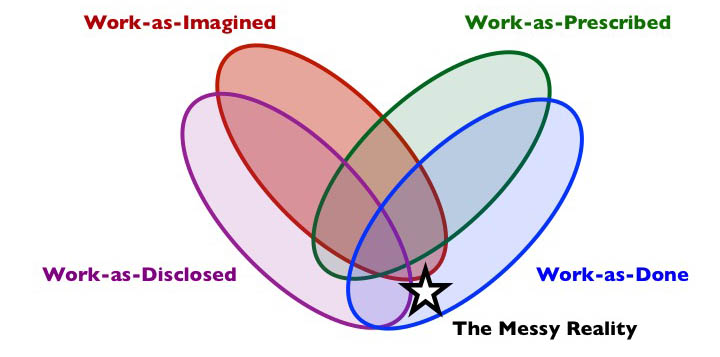

In my last post, I outlined some thoughts on four varieties of human work: work-as-imagined, work-as-prescribed, work-as-disclosed and work-as-done. As with most things, what is most interesting about these varieties concerns their relationships and interactions. Considering the various zones of the figure below – where the varieties overlap or don’t overlap – it is possible to recognise a number of archetypes, patterns or forms concerning the relationship between the varieties of human work, which will be familiar to many once seen.

In this post, I outline seven such ‘archetypes of human work’. This is not to say these are the only archetypes, and the archetypes do not necessarily characterise the zones that they inhabit. But they have shown themselves repeatedly in my experience of research and practice in organisations, and may well be recognisable to you. To sensecheck and exemplify the archetypes, a number of healthcare clinicians have kindly provided examples. These clinicians have helped to refine the archetypes themselves. If you have further examples – from any industry – please provide an example as a comment or get in touch. More examples will be added over time.

The seven archetypes that will be outlined are:

- The Messy Reality (this Archetype)

- Congruence

- Taboo

- Ignorance and Fantasy

- Projection

- P.R. and Subterfuge

- Defunct

These archetypes will be outlined in this and subsequent posts.

Archetype 1: The Messy Reality

Composition: work-as-done but not as-prescribed and usually not as-imagined (may or may not be as-disclosed).

Short description: Much work-as-done is not as prescribed (either different to procedures, guidelines, etc, or where there are no procedures), and is usually not known to others who are not at the sharp end of the work. The focus of The Messy Reality is the actual work and the messy details.

What is it?

The Messy Reality is characterised by the kinds of adjustments, adaptations, variations, trade-offs, compromises, and workarounds that are hard to prescribe and hard to see from afar, but can become accepted and unremarkable from the inside. Mostly, such variability is deliberate, but sometimes is unintended. As such, this archetype will be familiar to almost everyone.

The work-as-done that is characteristic of this archetype may or may not be disclosed by those who do the work. It is not necessarily secret (as is more characteristic of Taboo). The key point is more that work-as-done is not as prescribed, and probably not as-imagined or known by others. This archetype is common and applies to much specialist activity in most sectors, e.g., healthcare, banking, WebOps, shipping, and agriculture.

Why does it exist?

This archetype exists for a few reasons, associated with the nature of work-as-prescribed, work-as-done and work-as-imagined. Much work-as-done is not prescribed to any significant degree, especially where the work is so simple that it does not need to be prescribed, or so complex that it cannot be prescribed, even if attempts are or were once made. It is not necessary, possible nor desirable to prescribe all human work. Even if some major steps in a process are prescribed, much of the underlying or related activity is not. It can’t be.

This archetype provides important discretionary space in which practitioners can operate, since the various adjustments, adaptations, trade-offs, compromises, and workarounds that characterise work-as-done are necessary to meet demand under (often normal) system conditions involving degraded resources, inappropriate constraints, perverse incentives, goal conflicts, and production pressure. More generally work evolves over time, and prescribed work proves too inflexible or too fragile to cope with real conditions. Over the longer term, these adaptations may result in a drift from prescribed policy, procedure, standards or guidelines, assuming any such prescription is in place.

This archetype is reinforced by a lack of contact between those who do the work, and those who design, make decisions about, or influence the work (e.g., senior managers, purchasers, HR, regulators and policy makers), who may operate in the Ignorance and Fantasy archetype. Much work-as-done is taken for granted, neither observed nor discussed meaningfully outside of the immediate working environment, and so the messy details remain known only to those who do the actual work. The Messy Reality is therefore ignored or denied (perhaps glossed over with P.R. and Subterfuge). Even where there is an imagination of work-as-done (and associated system conditions), decision makers may turn a blind eye or encourage The Messy Reality, either because stuff gets done or because the costs of fixing sources of mess are seen as too great.

Shadow side

Work-as-done but not as-imagined by others is mostly unproblematic. The Messy Reality does provide important discretionary space for practitioners to meet demand. But The Messy Reality masks a multitude of degraded system conditions involving demand, pressure, capacity, staffing, competence, equipment, procedures, supplies, time, etc. To create flow, more adjustments, adaptations, trade-offs, compromises, and workarounds are required. Performance variability (short term fluctuations or longer term biases and trends), while necessary, may become problematic.

An underlying problem with The Messy Reality is its coexistence with the archetype Ignorance and Fantasy. When work-as-done is not understood by decision makers, problems and drift toward danger may well be invisible, both to the worker in-group (e.g., due to habituation) and to various out-groups (due to ignorance). For some time, a drift into failure may be invisible – masked by inadequate measurement, safety margins, or deliberate P.R. and Subterfuge, but practitioners will tend to feel – as a minimum – uncomfortable. Their concerns may be initially disclosed (formally via reporting systems or letters, or informally), but this disclosure is often discontinued if no timely and appropriate action is taken in response. This decline in disclosure convinces those at the blunt end that the problem no longer exists or was never really a problem, thus feeding the Ignorance and Fantasy archetype and associated blunt-end decisions that create systems of problems – messes.

When things go wrong in The Messy Reality, outcomes are often attributed to the choices that practitioners make, especially when these are different to the work-as-prescribed. Often, such attributions take insufficient account of context, and instead take the form of simplistic labels (‘violation’, ‘non-compliance’, ‘rule breaking’, etc), while choices made at the blunt-end of design, management, and regulation – which may influence, shape or encourage such sharp-end decisions – are rarely labelled in this way. This dynamic exists even in the absence of detailed prescription of work. For instance, if an organisation does not have a policy on a potentially problematic issue, such as the use of mobile devices in environments such as air traffic control, then practitioners could be blamed for their choices in case of an incident or accident, even when practices are known or imagined. Ultimately, The Messy Reality, can become a liability in terms of regulation and law, both to the organisation and to individual practitioners and those they serve.

In some cases, The Messy Reality may represent a realm of poor practice where there is little care for professional conduct, and may even represent grossly negligent or unethical or illegal activity. This is, however, is not representative of the archetype as a whole.

Examples (Aviation)

(New examples are added to the top)

Time Pressure. The list of mandatory content that must be covered during recurrent simulator routines is extensive. Trainers and Examiners are always under time pressure which leads to an inevitable trade-off between learning and content completion. The messy reality can be a highly variable and rushed experience for pilots depending on the priorities of the trainer. For example, comparing two occasions when I asked for more practice at a manoeuvre that I had ‘passed’ in my check. On the first occasion the trainer made it a priority, I got the extra practice I wanted and my performance improved. On the second occasion I was told that I could ‘un-pass’ myself if the practice didn’t go well, so we moved on and the opportunity to practice something I needed was replaced by something that I didn’t need.

Anonymous, Professional Pilot

Examples (Healthcare)

(New examples are added to the top)

Nursing care in in medical wards is a prime example of the messy reality of care.

Nurses and employers imagine a person centred assessment of needs, with careful supervision of medications given at times that suit individual patients. The imagined process involves nurses checking the patient’s prescription, checking the appropriateness and the interactions with other drugs, checking the patient’s identity bracelet against the prescription record and watching the patient ingest the medication before signing the administration record. This process is imagined to catch any prescription errors, ensure medication is given to the correct patient in a timely fashion and avoid any medication errors.

Medications are administered by registered nurses who can have 10 or more patients under their care. As patients increasingly have more than two long term conditions, many medications may be taken at any one time. Some patients (particular the increasing number with dementia) will have lost or removed their identity bracelets but still need their medicines. New patients may not have had all their medications prescribed and the nurse has to decide the risks of not giving a critical medicine against the need to have a formal hospital prescription.

The time taken to check the record and the patient’s identity and then watch them ingest all the medication can be significant (especially with frail people and those with dementia or delirium). With ten or more patients, plus interruptions for essential other activities such as vital signs and responding to deteriorating patients, a drug round can take up to two hours meaning that the last patient can get their medications two or more hours later that intended.

Medications are increasingly prescribed electronically. The software determines the time that the medication should be administered, without regard to the routine patients have established for themselves at home or the routines of the ward. The system cannot be altered by the nurses and so the administration record has incorrect times when nurses create workarounds for safety reasons, e.g. change the time of insulin administration to meet the patient’s eating habits, or the arrival of meals on the ward, or administer medications to patients with Parkinson’s Disease according to the personal pattern they have developed to give them the maximum mobility.

Anonymous

Our 72 bed PICU provides care to critically ill children (and adults with diseases of childhood) in a freestanding children’s hospital in the US. Medication administration (in contrast to prescribing or dispensing by a pharmacists) is a step that happens dozens, if not hundreds, of times a day.

Work-as-Imagined: While teaching across the US, I have queried nurses, physicians, hospital administrators and pharmacists about how many steps are involved in the work of a nurse administering a medication in the PICU. The typical response is 3-10 steps with a rare outlier response of “30 steps”.

Work-as-Prescribed: The hospital policy and procedure dedicates less than two single-spaced pages to medication administration. These two pages include the steps for using bar coding technology for medication administration.

Work-as-Done: As part of a federally funded grant (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality RO1 HS013610), we studied medication administration in our then 30-bed PICU. The findings I share here are prior to implementation of bar coding technology.

Trained graduate students in Industrial Engineering and Human Factors shadowed nurses capturing the various decision points and actions during their work of medication administration. Once we reached saturation with no new findings, we created a flow document and shared this with focus groups of the same nurses, who provided feedback to improve the accuracy. The final flow document (after incorporating the nurses feedback) was 64 pages long of various permutations, decision points and actions. The PICU nurses themselves validated the findings while admitting they had no idea how complex their work was.

Matt Scanlon, Professor of Pediatrics, Critical Care, Medical College of Wisconsin

Anaesthetists remain with a patient throughout the duration of their anaesthetic; from the moment the patient first ‘goes to sleep’ until they ‘wake up’, often they will be working as a solo anaesthetist forming part of the larger theatre team. Surgeons usually fit their food and rest breaks into ‘natural breaks’ in the operating list for example; when the patient is being anaesthetised, has been anaesthetised and is being positioned for surgery or is being taken to recovery. Theatre nursing staff usually have a structured rotation system to provide breaks.

As an anaesthetist is always with a patient, or preparing to anaesthetise the next patients there are no ‘natural breaks’. Many hospitals have no formal structure in place to provide breaks for anaesthetists working a ’solo’ list, this leaves the anaesthetist with the choice of stopping the list for their lunch break – likely to result in cancellation of patients due to running out of theatre time or eating and drinking in the anaesthetic room which is against infection control policy.

As a result anaesthetists will have drinks and snacks in the anaesthetic room immediately adjacent to the operating theatre so they can still see the patient and the monitoring but are not ‘in theatre’. This is widely known by clinical and managerial staff as there are insufficient anaesthetists to cover the workload that is required and provide breaks for colleagues. There are cases where anaesthetists have been subject to disciplinary action for such behaviour, despite the organisation offering no breaks.

Anonymous

The UK GMC clearly states that all medical notes should clearly and legibly document who has made a decision, who is documenting the decision and when the decision was made. This is widely published by the GMC in ‘Good Medical Practice’ and all healthcare professionals are aware of this.

Despite this guidance it is known and repeatedly demonstrated in medical literature that this is not the case. This is a danger to patient safety and a contributor to system failure.

Hospital policies repeatedly include this guidance despite it being well understood that it is commonly not achieved.

Anonymous

Pre-printed operating lists are generated for elective surgery. These lists contain the name, unique identifier of each patient along with a brief description of the planned procedure. Unfortunately, the procedure description is often too vague or inaccurate and the specifics of the procedure and the equipment required to support this are often not available to the perioperative team until the pre-list brief on the morning of surgery. Often this can be complicated by patients being admitted on the day of surgery when additional information becomes available regarding the patient’s condition becomes available that requires a change to the order of the operating list.

John Stirling, RGN, MFPCEd

When working as a paediatric intensive care (PICU) nurse we regularly admitted more children than we had beds for. The environment accommodated 12 sick children in one section and 2 children in side rooms for highly infectious patients or patients that had severe burns. There were guidelines for how many patients we were supposed to have and how they needed to be nursed in order to be safe (1:1 nursing ratio) but we would regularly fit two more children into the 12 bedded bays i.e. 14 beds – squeezing them in by another child and sharing the nursing so 1:2 nursing ratio. This was done because of the limited numbers of PICU beds across London and if all PICUs were full then they would either have had to travel long distances which was extremely life threatening or to be admitted to us under ‘risky’ but ‘less risky than travelling’ conditions.

Suzette Woodward, National Clinical Director, Sign up to Safety Team, NHS England @SuzetteWoodward

“Nearly four months after Connor died, the Trust commissioned an independent investigation into what happened. … Southern Health finally agreed for the Verita report Independent investigation into the death of CS to be published on 24 February 2014 after some meithering around the suggestion that a ‘summary’ of the report should be published instead of the actual report. … There were 23 findings, including:

F1 We found no evidence that an epilepsy profile was completed when CS was admitted to the unit. This was a key omission.

F5 There was no comprehensive care plan to manage CS’s epilepsy.

F8 Staff should have increased their vigilance and monitoring of CS after his suspected seizure. This was a missed opportunity.

F11 We found no documentary evidence after 3 June that CS was observed in the bath every 15 minutes.

F12 Three of the 17 members of the unit team received training updates in epileptic care between October 2010 and August 2013.

F19 The unit lacked clinical leadership.“

Extracts from Justice for Laughing Boy. Connor Sparrowhawk – A Death by Indifference, Jessica Kingsley Publishers, pp. 115-121, by Sara Ryan, Mother of Connor Sparrowhawk, also known as Laughing Boy or LB, who died was found dead in a specialist NHS unit on July 4th 2013.

There are published guidelines (Royal College of Radiologists) relating to the number is scans, CT/MRI etc, an individual radiologist would be expected to report. These are not limits but rather guidelines. In my experience, these numbers are often exceeded in daily practice due to the volume of scanning being done.

Anonymous, Radiologist

Guidelines are often published relating to ‘best practice’ when managing a particular condition. An example would be acute stroke or head injury. These guidelines are often international and come from countries with very different health care models. They are not always followed, mainly due to lack of resources (eg out of hours MRI or staffing issues).

Anonymous, Radiologist

For safety purposes MRI staff know that they should not work alone but often leave their colleague alone, for example, to see admin. staff to sort out appointments etc. instead of asking admin. staff to come to them, which would be the safest thing. There is the expectation on their part that it will be fine for the short period they are away from the unit. MRI Staff often witness and/or cause near misses in the MRI scanning room and know that they should report them but, due to either a lack of time or lack of understanding on the importance of reporting them they very rarely get reported.

Anonymous, Radiographer

Staff are told to put MRI-unsafe wheelchairs/trolleys/beds from the ward out into the reception area (so Zone 3 is clear for a clinical emergency and only has MRI-safe trolleys in it) but the radiographers don’t do this because: a) it takes time to put it out to reception area; b) reception staff complain that the reception/waiting area is cluttered and too small. It is a problem of additional effort on radiographers part, and MRI safety versus reception staff who think they know best.

Anonymous, Radiographer

When the surgical team book a patient for theatre, they are supposed to discuss this with the anaesthetic team, to explain the indication for surgery, the degree of urgency and any medical conditions the patient has. The anaesthetic team should therefore be a central point who are aware of all the patients waiting for theatre to help with appropriate prioritisation. In reality this only happens if they happen to see an anaesthetist when they book the case. More often than not, cases are “booked” with no discussion with the anaesthetist and often the cases are not ready for theatre (may need scans first for example) or may not even need an operation. This only becomes obvious when the anaesthetist goes to review the patient, or perhaps even later. Despite many organisations having guidelines about this, it still seems to happen.

Emma Plunkett, Anaesthetist, @emmaplunkett

Certain clinical situations are volatile, uncertain, complex, ambiguous (VUCA) and time critical and they can highlight different aspects of ‘The Messy Reality’. For example, a patient with a ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm, if they reach hospital alive, will require immediate transfer to theatre for the life threatening bleeding to be stopped and a new vessel to be grafted into place. The complex and dynamic nature of the case deems that it cannot be prescribed and so the practitioner has to operate within the discretionary space. This allows the practitioner the necessary freedom to treat the changes as they arise and potentially to deviate from ‘standard operating procedures’ (SOPs). These SOPs are ordinarily designed for non-emergency work and have a number of ‘safety steps’ inherent within them. There are important steps such as identifying the patient, procedure and allergies and form part of the wider WHO ‘five steps to safety’ but also other points less critical but important, especially in the non-emergency setting. It is commonplace for the practitioner to deviate from the SOPs and to perform an ad-hoc, yet necessary, streamlining of this process in order to proceed at the appropriate pace and to treat physiological changes as they present themselves. This can give rise to a number of issues. Firstly, I have known this deviation to create friction amongst the team at this critical time that is generally not helpful in both proceeding with the work and maintaining team harmony. Secondly, if the outcome for the patient is poor and the case is investigated, I have known for practitioners to be admonished for their deviation from the SOPs, although they nominally relate to the non-emergency setting. This is in stark contrast to if there is a good patient outcome as the deviation is often not even noted, or highlighted as potentially being intrinsic to the positive outcome. Lastly there is often a corporate response that seeks to prescribe the work that is by definition VUCA and cannot be prescribed. Ultimately, I believe that on balance practitioners benefit from The Messy Reality as it is when the work is at its most complicated and cannot be prescribed that autonomy and professional judgment can be exercised most readily for the benefit of the patient.

Dr Alistair Hellewell, Anaesthetist, @AlHellewell

The ‘normalised’ unsafe practice of hyperventilation during cardiac arrest management provides a comprehensive example of The Messy Reality archetype. It has become evident, from analysing retrospective observational data, that during the procedure of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), medical practitioners (usually anaesthetists) almost always deliver too much pressurised oxygen/air to the lungs of patients (both adults and children). Traditional Safety-I concepts may regard this as a ‘violation’, in that that this practice continues to occur despite a succession of recommendations in international guidelines to the contrary, supported by the established and widespread provision of systematic, organised education and training. However, when directly questioned, anaesthetists demonstrate a clear, functional knowledge that such practice is detrimental to patient outcome. When contemplating this behaviour we must consider the following. Firstly, there is no intention for airway management practitioners to deliberately hyperventilate a patient. Secondly, these clinicians do not know that they are hyperventilating patients during the period that it is actually happening. Thirdly, there is not ordinarily any recognition or acknowledgement that they may have hyperventilated the patient after the clinical intervention has been discontinued. Despite the fact that this issue is widely known to anaesthetists, others (particularly at the blunt end) would generally be ignorant of the issue.

Ken Spearpoint, Emeritus Consultant Nurse, @k_g_spearpoint

Radiology request forms are meant to be completed and signed by the person requesting the procedure. In the operating theatre, the surgeon is usually scrubbed and sterile, therefore the anaesthetist often fills out and signs the form despite this being “against the rules”. Managers in radiology refused to believe that the radiographers carrying out the procedures in theatre were “allowing” this deviation from the rules.

Anonymous.

The use of clinical early warning scores is well established in secondary care. More recently, the use of the National Early Warning Score in primary care has been promoted as a way to aid the identification and appropriate management of sepsis. A score is calculated based on the value of each of the following physiological parameters: temperature, pulse rate, blood pressure, oxygen saturations, respiratory rate and level of consciousness. When interviewed, most general practitioners (GPs) stated that, although they do not calculate the overall NEWS score, they always record the relevant observations when they are concerned about sepsis. On analysis of referral letters of adults admitted with an infective cause from out-of-hours primary care to secondary care, all physiological parameters necessary for the NEWS score were recorded in 50% of patients but when the admission diagnosis was given as sepsis or possible sepsis, the values were only complete in 30% of cases. When this is explored with GPs using specific cases it becomes clear that often the decision for rapid admission is made on temperature, pulse and often the ‘look’ of the patient. Rather than measuring other parameters (such as respiratory rate) the GP decides to start arranging admission as further evidence is not needed to guide their next action. This is a more efficient if less thorough approach. (Early findings of work – unpublished at present.)

Duncan McNab, General Practitioner, @Duncansmcnab

Hospital policy is that free samples of drugs may not be accepted from pharmaceutical companies, and that all supplies of drugs should be ordered and received via the pharmacy department. However, drug company representatives have been known to bypass this by directly offering/sending free drug samples directly to consultants.

Anonymous, Pharmacist

Pharmacists and technicians provide support to care homes to carry out medication reviews and support repeat ordering. One piece of documentation we use to support this is the Medicines Administration Record (MAR). These are generated by the community pharmacy, which supplies the medication. This in itself is not deemed a care home confidential document until such a time as the care home starts to use them to note administration of medications. At this point, access to it by anyone but care home staff requires consent. We do obtain patient/welfare/proxy consent to undertake our work, but technically, as the MAR sheets are issued monthly and can be different on a monthly basis, we should be getting monthly consent. This would make it unworkable and unmanageable.

Anonymous, Pharmacist

Examples (Petrochemical)

(New examples are added to the top)

At a petrochemical loading dock, it was well known at the work crew level that an operator would commonly drive out of the site and meet the incoming operator as they were driving in on the road, to hand over the keys. This “saved time” and shortened the work day of both people, but left the dock plant unattended for around 10 to 30 minutes, including while loading was in progress. Management became aware of this practice after new security cameras were installed. However, there was an agreement with the unions that the security camera recordings could not be used other than for security, so the information could not be used to make supervisory or management decisions or for disciplinary processes. Therefore nothing was done to change this practice.

Anonymous

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

9 thoughts